GAP President John Dwyer speaks about GAP’s participation in the original Trailblazer trial, and our goals for TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2.

It has been clear for a while that anti-amyloid antibodies can sweep plaque from the brain, but until now the question of whether this slows cognitive decline has remained hotly contended. Despite some positive signals from four such antibodies, the data have been messy and hard to interpret. At the 15th International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases, held virtually March 10–14, Mark Mintun of Eli Lilly & Company presented the cleanest data yet on this question. In a Phase 2 trial, the company’s anti-amyloid antibody donanemab met its primary endpoint. Participants did not get better. Even so, donanemab slowed their decline by an average of 32 percent on a combined cognitive and functional measure.

- In a Phase 2 trial, donanemab completely cleared plaque in two-thirds of participants.

- Their cognitive decline slowed by a third, meeting the primary endpoint.

- The treatment appeared to nudge down tangles, and worked best at low tangle loads.

Donanemab banished plaque from the brain in a majority of participants, while nudging down the rate of neurofibrillary tangle accumulation in the frontal cortex and other regions. The trial included several innovative elements, such as screening participants by tangle burden, using tau PET as a secondary outcome measure, and stopping dosing once amyloid was gone. The AD/PD presentation fleshed out previously announced topline data (Jan 2021 news). Full results were published March 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine (Mintun et al., 2021).

Most Alzheimer’s researchers welcomed the findings. “This was the first [disease-modifying] AD drug to meet a clinical endpoint in a Phase 2 trial,” noted Ron Petersen of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Michael Weiner of the University of California, San Francisco, found the broader implications encouraging. “In my view, together with data from other trials, this study strongly confirms the ‘amyloid hypothesis’ and demonstrates that treatments aimed at amyloid can slow cognitive decline and modify the progression of AD,” he wrote (full comments below).

At the same time, researchers emphasized that, as with other anti-amyloid immunotherapies, the cognitive benefit was small. “The donanemab story is the most encouraging news on the amyloid front, ever, but whether the effect size is clinically meaningful is questionable,” David Knopman at the Rochester Mayo clinic wrote to Alzforum (full comment below).

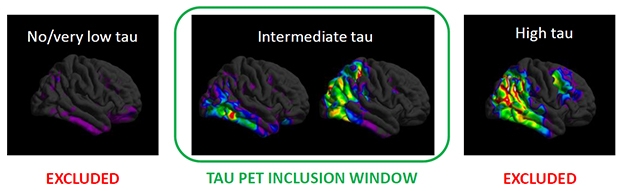

Screen By Path. People with few tangles (left) have too little cognitive decline to measure, while those with a heavy tangle burden (right) may have worsened beyond the reach of an anti-amyloid drug. Selecting for the just-right tangle load (middle) may have helped the donanemab trial succeed. [Courtesy of Eli Lilly.]

Plaque-Busting Power

Donanemab is unique among AD immunotherapies in that it targets a modified version of A? that has a pyroglutamate attached to the N terminus. This pathological form of A? is highly prone to aggregate, depositing in the core of all amyloid plaques, but is found nowhere else in the brain (Dec 2009 conference news; Nov 2010 conference news; Dec 2012 news). In Phase 1 trials, donanemab busted up plaques fast, in many cases clearing all deposits within six months (Aug 2018 conference news; Dec 2019 conference news).

However, even dramatic amyloid clearance has not translated into a clear cognitive benefit in past Phase 2 and 3 immunotherapy trials. In a company call with investors, Lilly’s chief scientific officer, Dan Skovronsky, said part of the problem in obtaining definitive cognitive results may arise from the heterogeneity of AD trial populations, with participants worsening clinically at different rates. To limit this variability, the researchers screened participants in their 18-month Phase 2 Trailblazer study using tau PET. They believed this might work because previous studies had shown that a person’s baseline tau PET signal predicted his or her speed of subsequent cognitive decline.

People with flortaucipir SUVRs below 1.1 were excluded from this trial, since studies have shown almost no cognitive decline in this group within the time span of this trial. Those with SUVRs above 1.46 were also excluded, as the researchers hypothesized that tangle pathology in their brains would be too advanced for an amyloid therapy to do them any good (see image above). Mintun estimates that 30 to 45 percent of people with early symptomatic AD fall into the intermediate tau range where anti-amyloid therapy might be effective.

The researchers ended up enrolling 257 people with this intermediate tangle burden at 56 sites across the United States and Canada. Participants were predominantly white, with an average age of 75, and about three-quarters carried an APOE4 allele. All had early symptomatic AD and were amyloid-positive by florbetapir PET scan, with a mean MMSE of 23.6. Mintun noted that this cognitive average is lower than for many other trials in early AD, where the cutoff for inclusion is often 24, and the average score higher. Selecting participants based on tangle pathology rather than clinical criteria may have allowed for a wider range in clinical status, he suggested. Because of cognitive reserve, people with similar levels of brain pathology often differ in the degree to which their function is preserved (Aug 2017 conference news). “Some patients who would be considered too impaired for inclusion in an early AD trial might still be at an early stage of pathology and respond to treatment,” Mintun noted.

Half the participants, 131 people, received donanemab, the other 126 placebo. Doses were titrated up rapidly for quick plaque clearance, with participants receiving 700 mg for the first three monthly infusions and 1,400 mg per month thereafter. Participants underwent florbetapir scans at weeks 24 and 52 to assess their progress. If their amyloid burden fell below 25 centiloids—the level in healthy young controls—their donanemab dose was lowered to 700. If it fell below 11 centiloids, or below 25 for two consecutive scans, they were switched to placebo.

Why stop dosing? Pyroglutamate-A? only occurs in plaques, so once the target is gone, there is no need for further treatment, Mintun said. Commentators applauded this limited course of treatment, given the expense and side effects of antibodies. “That patients could be withdrawn from the treatment is a remarkable prospect for broader use,” Knopman wrote. Petersen suggested it would make AD easier to manage chronically. “We may be able to lower amyloid levels, monitor the patients, and if the levels rise, re-dose. This would be akin to giving a booster immunization,” Petersen said.

In Trailblazer, the baseline amyloid burden was 108 centiloids in the active group and 101 in the placebo group. It stayed stable in the placebo group over the course of the study. In the active group, it dropped by an average of 85 centiloids. The bulk of the clearance came early, with an average drop of 68 centiloids by week 24. At that time, 40 percent of the treatment group were switched to placebo. This rose to 60 percent by 52 weeks and 68 percent by 76 weeks. In other words, two-thirds of participants were amyloid-negative by the end of the trial. Mintun noted that plaque clearance at 18 months was about twice that seen with aducanumab, in agreement with earlier trial results suggesting that donanemab clears plaque more aggressively than do other investigational antibodies.

In an ongoing open-label extension trial, participants who still have plaque, as well as previous placebo patients, will remain on donanemab treatment until they, too, become amyloid-negative. Researchers will follow all patients to assess how they fare over time.

Detecting a Cognitive Signal

Did this clearance translate into a better-functioning brain, though? To answer this, the researchers chose as their primary outcome measure the integrated Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale. Lilly had developed the iADRS by combining the ADAS-Cog13 with the ADCS-instrumental Activities of Daily Living scales (Wessels et al., 2015). In the Phase 3 solanezumab Expedition studies, this combined cognitive and functional scale yielded more consistent results than did the CDR-SB, Mintun said. Likewise, in the placebo arm of Trailblazer, the iADRS scores reflected a constant rate of decline, whereas the CDR-SB posted variability from timepoint to timepoint. Mintun said the CDR-SB has proven noisy and unreliable in other large AD studies, as well, for example giving one positive and one negative result in the aducanumab Phase 3 program. “We believe the iADRS is a more consistent and sensitive measure to detect treatment differences than other AD scales,” Mintun said.

In Trailblazer, participants started out with an average iADRS score of 106, with the placebo group declining 10.06 points by the end of the trial, and the active group by 6.86. The treatment groups started to diverge at 24 weeks, around the time plaque clearance became dramatic. The difference between groups reached statistical significance at 36 weeks and maintained that for every timepoint thereafter, with a final p value of 0.04. The one-third slowing of decline is modest. It would translate to a six-month delay in disease progression over the course of the 18-month trial, Mintun noted.

All secondary clinical measures trended in favor of donanemab, but only the ADAS-Cog13 reached significance at p=0.04, with an average slowing of 39 percent. On the CDR-SB, decline slowed only by 23 percent, on MMSE, 21 percent, and on ADL, 23 percent. As with the iADRS, active groups first diverged from placebo at 24 or 36 weeks. Mintun noted that the 23 percent slowing on CDR-SB is no smaller an effect size than has been seen to date in AD trials.

Among individual participants, the pattern of plaque clearance varied, with some getting a large initial drop and others a steady decline. This made no difference to the cognitive benefit, Mintun said.

Given that donanemab completely cleared plaque, the researchers acknowledged that a 32 percent slowing may represent the most it can achieve in people at this stage of AD. “This is probably the ceiling for an amyloid-lowering drug,” Skovronsky said. To do more for patients, researchers likely will have to treat earlier in a prevention paradigm, or combine anti-amyloid treatment with an anti-tau drug, he suggested.

Less Tangles, More Cognition. Trial participants with the lowest tangle burden (left) reaped the biggest benefit, while those with the most tau pathology (right) had none. The findings may help refine selection for future trials. [Courtesy of Eli Lilly.]

When Plaques Vanish, Tangle Formation Slows

About that tau … unlike the loose association amyloid has with cognition, tau tangles are closely linked to cognitive decline. Did donanemab affect them? On a measure of global tau PET, the answer was no. Tau tracer uptake climbed in both groups throughout the study, with the active treatment group gaining only 10 percent less than the placebo group, a nonsignificant difference.

When the researchers looked at regional tracer uptake, they saw something different. Tangle accumulation slowed by 59 percent in the frontal lobe, by 45 percent in the parietal lobe, and 32 percent in the lateral temporal lobe. These differences were statistically significant, the first two at p=0.002. In mesial temporal lobe, the placebo group had no change in tangles, but the donanemab group saw a slight but significant drop. The groups were no different in the occipital lobe.

Plaque clearance was linked to the slowing of tau pathology, Mintun noted. Participants who reached amyloid-negative status during the trial had more slowing on tau PET than those who didn’t. It is unclear mechanistically how plaques affect tangles. Mintun suggested that some toxic aspect of amyloid may be responsible for accelerating tauopathy, such that removing it puts on the brakes. A recent study implicated microglial inflammation as the culprit linking the two pathologies (Nov 2019 news).

Regional tangles, particularly in the frontal cortex, also correlated with the cognitive outcome, with a higher baseline frontal tau signal predicting faster decline on the iADRS. “We’ve provided data to validate regional tau spread as an important surrogate for disease progression and drug effect,” Skovronsky said.

What about the idea that baseline tangle load influences donanemab’s effect? To study this, the researchers stratified the active group into terciles based on their baseline tau PET. The lowest tercile, below 1.14 SUVR, drove most of the cognitive benefit from donanemab; this group’s decline slowed by almost half. The intermediate tercile showed little treatment benefit, and the highest, above 1.27 SUVR, none (see image above). These subgroups were too small for statistical significance, and the analysis is exploratory, Mintun said.

Nonetheless, Lilly researchers believe the data may help explain why this trial succeeded. “Excluding patients with high tau could be a key factor in the efficacy of donanemab. We believe it’s important that all future Alzheimer’s trials and therapies be based on the pathological stage of the patient, as is done in oncology,” Mintun said.

Others wondered whether the tau range should be narrowed further for Phase 3, since people with an SUVR between 1.27 and 1.46 did not benefit. Skovronsky said Lilly will keep the range the same for Phase 3. The idea is to replicate the Phase 2 findings, and Phase 3 will have more power to detect treatment effects.

Gil Rabinovici of UCSF was intrigued by these data. “This suggests that the primary role of amyloid-lowering therapies may be in patients in whom tau is not yet widespread, most of whom will be in the preclinical or very earliest clinical stage. Progress in blood-based biomarkers should greatly facilitate the detection of earliest-stage AD in an accessible, equitable and cost-effective manner,” he wrote (full comment below).

ARIA Still An Issue

Safety data in the Trailblazer trial was similar to previous donanemab studies and to other antibodies in this class. A quarter of the active group, 35 people, developed the brain edema known as ARIA-E. In eight people, about 6 percent of those on donanemab, it was symptomatic. People taking the antibody also developed more superficial siderosis, iron deposits that form on subpial surfaces due to small brain bleeds, than controls, at 14 percent versus 3. They had more ARIA-H, or microhemorrhages, at 8 percent versus 3, and more nausea, 11 percent versus 3. Donanemab administration caused infusion reactions in 10 people, though most were mild or moderate, did not require intervention, and did not reoccur. There were no differences in serious adverse events or deaths between groups.

Erik Musiek of Washington University, St. Louis, noted that the ARIA-E incidence was similar to that in people taking low-dose aducanumab, while the ARIA-H incidence was lower than the 17 percent reported for aducanumab (comment below). Rabinovici believes the overall safety profile of donanemab would be acceptable to most AD patients.

More people on donanemab than placebo, 40 versus nine, discontinued treatment, most due to ARIA-H or superficial siderosis. Most who stopped treatment remained in the study, and their data were included in the final outcome measures. Skovronsky said that those who stopped treatment due to ARIA had already achieved a high degree of plaque clearance, and attained the same drug benefit as those who remained on therapy.

Russell Swerdlow of University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, noted that the occurrence of symptomatic ARIA can confound trial results by inadvertently unblinding participants. Because APOE4 carriers are more likely to develop ARIA and stop treatment, the removal of such fast progressors from the treatment arm also could skew results. “Hopefully the planned Phase 3 studies will implement measures to take into account these potential confounders,” Swerdlow wrote (full comment below).

Lilly researchers contend that ARIA barely affected their Phase 2 results, since an analysis of donanemab subgroups with and without ARIA-E found no difference in their respective rates of decline, and people who stopped treatment were included in the final analysis.

As in the earlier donanemab trial, 90 percent of participants developed anti-drug antibodies. These did not appear to affect treatment efficacy, but Skovronsky acknowledged that it would be better to have a treatment that does not produce them. Lilly is testing such a version of donanemab, dubbed N3pG4, in clinical trials, but Skovronsky said Lilly intends to bring donanemab to market.

Phase 3: Stick With What Worked

Based on the Trailblazer data, Lilly researchers have made several changes to Trailblazer 2, which has been enrolling since last summer. Instead of a Phase 2 trial with 500 participants, it will become a Phase 3 with 1,500. Scientists hope the larger sample will boost the chance of success on secondary outcomes, increase power to see subgroup effects including in the tau tercile groups, and generate a larger safety database, Mintun noted. Trial sites have been enrolling people with both intermediate and high tau scans, but will now limit the primary efficacy analysis to 1,000 participants with intermediate tangle pathology. Data from 500 people with a higher tangle load, above 1.46 SUVR, will help inform future treatment guidelines, Mintun said.

Lilly had previously considered using the CDR-SB as an endpoint for the new trial, but will stick with iADRS instead. In answer to an investor question, Skovronsky said this was discussed with regulators at the Food and Drug Administration. In one change from Phase 2, however, Lilly will analyze efficacy using the Disease Progression Model (DPM), which generates a probability of disease progression based on data from every timepoint across the trial, rather than looking only at the last timepoint, as the standard model does. Mintun said the final timepoint in AD trials is often the noisiest, so he believes a DPM analysis will be more reliable. In the Phase 2 trial, a DPM analysis gave similar results to the standard method, with every endpoint favoring donanemab.

The Global Alzheimer’s Platform will help speed recruitment for Trailblazer 2. GAP co-founder John Dwyer, who leads the Washington, D.C.-based organization, noted that the original Trailblazer was the first trial GAP worked on. His goal is for Trailblazer 2 to enlist 130 sites worldwide, including many in the GAP-North American network. “We expect to have an immediate impact on TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2, and one of our priorities will be reaching potential participants from diverse communities,” Dwyer wrote to Alzforum.

Skovronsky expects Trailblazer 2 to complete enrollment in the second half of 2021 and read out in the first half of 2023. Lilly will explore its chances for accelerated regulatory approval, but Trailblazer 2 will complete regardless. “Replication will answer important questions for the field, such as confirming subgroups that show no benefit,” Skovronsky said. Still, because the first Trailblazer was designed as a registration trial, he expects a second positive trial could be sufficient for approval.

If donanemab only helps people up to a certain tangle load, how large is the estimated patient group? Skovronsky noted that 4.5 million people have early symptomatic AD in the United States, 5 million in Europe, and 4 million in Japan. If 30 to 45 percent meet the criteria, that would be 1–2 million people in each place.

The FDA is considering a licensing application from Biogen for its anti-amyloid antibody aducanumab (Feb 2021 news). Will the donanemab data influence the agency? Rabinovici, at least, thinks it should not. “While these results are encouraging for the overall drug class, the FDA needs to consider the aducanumab EMERGE and ENGAGE data on their own merits. There are significant differences between aducanumab and donanemab in the antibody-targeted epitopes, study design and patient populations, and one cannot generalize results from one trial to the other,” he wrote.

Others think eventual approval of an anti-amyloid therapeutic is now inevitable. “The donanemab results provide powerful support for the amyloid therapeutic hypothesis; this strategy will bring the first disease-modifying drugs for AD into clinical use,” Paul Aisen of the University of Southern California, San Diego, wrote to Alzforum

—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

Originally posted by Alz Forum on March 19, 2021.