Emerging biomarkers and digital tools are unlocking earlier and more accurate diagnosis

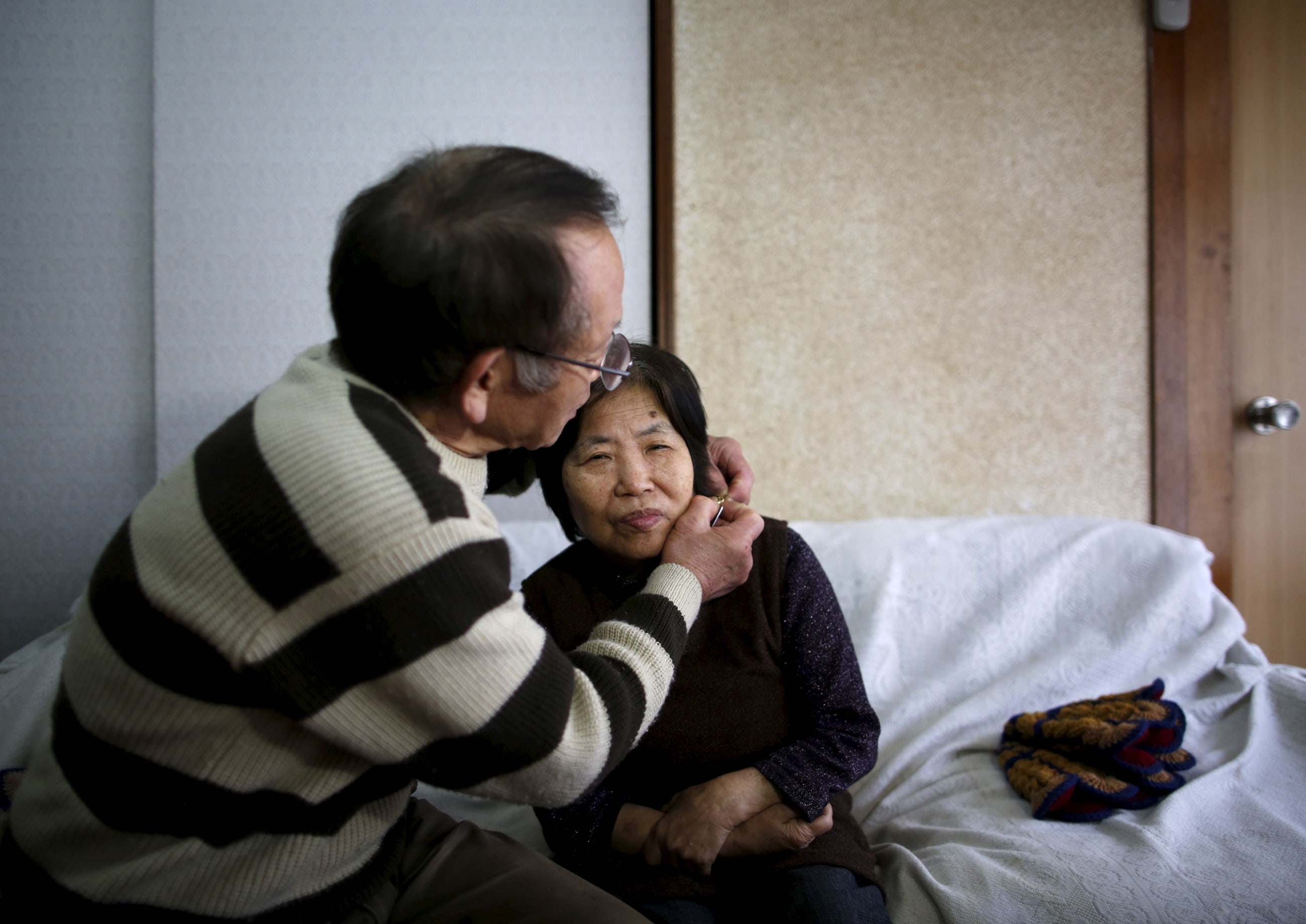

Teresa, 75, an Alzheimer’s patient and former businesswoman, poses for a photograph inside the Alzheimer Foundation, in Mexico City, Mexico, on April 19, 2012.REUTERS/Edgard Garrido

by Lydia Wu, Jennifer Panlilio, Melissa Lee, Laura Nisenbaum, Aishu Sukumar

December 10, 2025

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias affect more than 55 million people worldwide, a number expected to double by 2050 as populations age. Beyond its devastating personal toll, dementia costs the global economy more than $1.3 trillion a year.

Disease-modifying therapies such as Leqembi and Kisunla have recently emerged as treatment options. These work by binding to toxic molecules associated with the disease, triggering the body’s immune system to clear them. Although they have been shown to moderately slow disease progression, their effectiveness hinges on timely and accurate diagnosis. Alzheimer’s, however, is still routinely misdiagnosed or diagnosed too late, often after irreversible brain damage has occurred.

This could soon change. Recent breakthroughs in blood-based biomarkers, along with advances in digital tools, molecular profiling, and multimodal approaches, could allow for earlier and more precise diagnoses. Collectively, these tools can help detect Alzheimer’s disease early enough to intervene.

Outdated Traditional Tools, Delayed Treatment

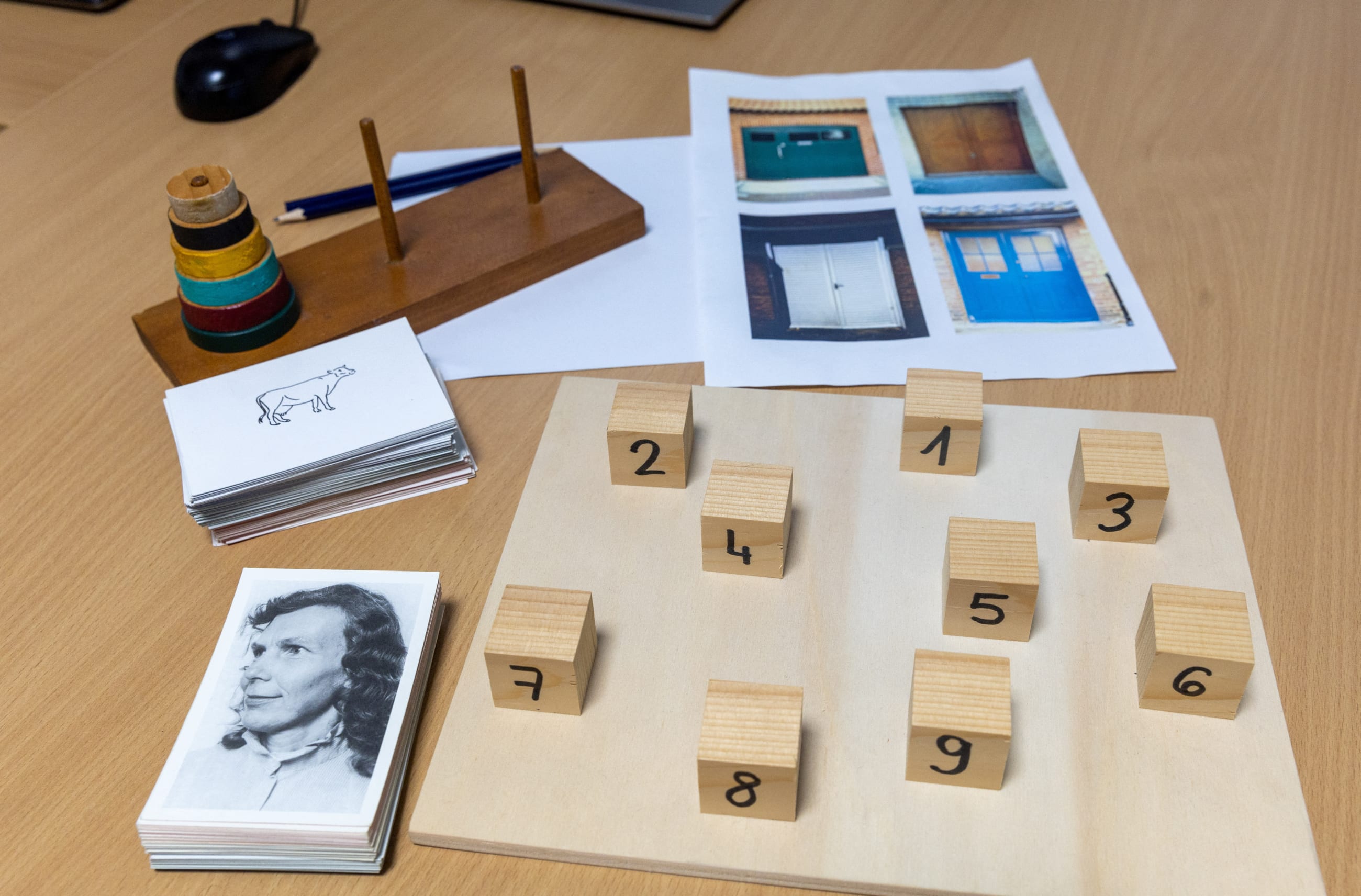

Traditional Alzheimer’s diagnostics rely on a combination of methods: cognitive testing, cerebrospinal fluid analysis through lumbar puncture, and brain imaging such as positron emission tomography (PET) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Despite being effective in specialized settings, these tools have significant limitations, resulting in an estimated 75% of dementia cases going undiagnosed worldwide.

For example, brain PET scans can cost between $1,200 and $10,900 in the United States. Lumbar punctures are invasive and burdensome for patients. Cognitive tests require specialists and may be subjective. Misdiagnosis is also a concern. Alzheimer’s can be confused with other dementias, depression, or even normal aging, especially when specialized testing is unavailable.

The Blood Biomarker Breakthrough: Simpler, Cheaper, Earlier

Game-changing new tools are emerging that could soon replace the need for costly brain scans.

In May 2025, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared the first blood test to help diagnose Alzheimer’s disease, a milestone that could transform the diagnostic landscape. This test, developed by Fujirebio, measures two proteins in the blood associated with Alzheimer’s pathology and has shown greater than 91% agreement with brain scans. It is intended to be used, in conjunction with other assessments, in a specialist setting such as neurology to diagnose Alzheimer’s.

Roche’s Elecsys test is another major advance in blood-based biomarkers. In October 2025, the FDA cleared this assay for use in primary care to help rule out Alzheimer’s. By expanding use from specialty to primary care setting, the test has the potential to further broaden access.

Although challenges remain around standardization and integration into clinical workflows, blood-based biomarkers show strong potential to simplify and accelerate diagnosis, possibly becoming a cornerstone of Alzheimer’s care in the coming decade.

Digital Biomarkers for Early Detection

Beyond blood biomarkers, digital biomarkers—data derived from everyday interactions with smartphones, wearables, and other devices—offer unprecedented opportunities for early detection of subtle changes in Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

App-Based Tests

Apps delivering digitized cognitive tests are gaining traction, allowing for repeated, low-cost assessments over time. These tools offer brief, gamified tasks that can measure memory, attention, executive function, and processing speed—key domains affected by Alzheimer’s.

Unlike traditional paper-based tests, digital assessments can be administered remotely and scored instantly, enabling broader access and more frequent monitoring. Although some leading developers in this space, such as Cognivue, are exempted by the FDA to aid cognition assessment, clinical adoption is still evolving.

Passive Monitoring

Everyday behavior can also provide valuable insights into cognition. Wearables and smartphones are increasingly used to track sleep patterns, movement, and location variability, all of which may correlate with cognitive changes.

Speech in particular is emerging as a powerful passive biomarker of early Alzheimer’s disease. Changes in word choice, meaning, and sentence structure can precede noticeable cognitive decline. In recent studies, speech-derived digital biomarkers could successfully distinguish between cognitively healthy individuals and those with mild cognitive impairment more than 80% of the time.

Although the field is nascent, initiatives such as SpeechDx are already playing a key role by building high-quality voice datasets. Harnessing the potential of speech markers and identifying ways to measure them passively without compromising on individual privacy and security could be game changing for early detection at scale.

If issues around data privacy and connectivity are addressed, digital tools have the potential to enable more accessible Alzheimer’s detection that could address gaps in global health systems strained by limited specialists and infrastructure.

Molecular Biomarkers for Precision Diagnosis

The need to better understand Alzheimer’s heterogeneous nature is also urgent. Cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s patients varies widely, differing in when symptoms appear and how quickly they progress. This variation often reflects the presence of other brain pathologies beyond classic Alzheimer’s. Emerging tools are beginning to be able to identify these subtypes, paving the way to a deeper understanding of the disease and more targeted care for patients.

Omics Approaches

One way to discover these diverse drivers of Alzheimer’s is the large-scale analysis of genes, RNA, or proteins, a term broadly named omics. By measuring thousands of molecules at once, these tools enable researchers to identify novel biomarkers that uncover mechanisms often missed in traditional single-molecule studies.

The Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium (GNPC) is driving a major advancement in this space. A public?private partnership, GNPC has created the world’s largest unified proteomic dataset focused on neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. It includes nearly 300 million protein measurements, connected when possible with clinical records, medical imaging, and genetic data. This unprecedented resource is poised to uncover novel blood-based biomarkers that can reflect the true biological complexity of the disease.

Extracellular Vesicles

Still in early development, diagnostics based on extracellular vesicles (EVs) may provide brain-specific information without the need for a spinal tap. EVs are tiny spheres released by cells that carry biological molecules such as proteins and RNA. Importantly, EVs released from brain cells can be detected in the blood, making it a powerful way to measure molecules directly linked to disease processes in the brain. A simple blood draw could provide access to critical clues about brain health, facilitating the development of minimally invasive diagnostics.

Although promising, this field is still emerging and requires further studies and development before it can be applied clinically.

Multimodal Approach: Combining Digital and Molecular Biomarkers

Ultimately, no single biomarker can capture the full complexity of Alzheimer’s disease. The future of Alzheimer’s diagnostics may lie in multimodal (multifaceted) approaches that combine blood biomarkers, digital data, imaging, genetics, and clinical history to provide comprehensive assessments.

Given data availability and standardization, previous multimodal research centered on combining MRI and PET imaging, achieving up to 99% in diagnostic accuracy. As additional datasets including omics, blood-based biomarkers, and digital assessments become more robust, new models can be trained on these integrated data streams, opening the door to earlier and ultimately more personalized diagnoses.

Bridging the Gap: Challenges to Clinical Translation

As these exciting technologies mature, one challenge remains: translation into real-world, global practice.

Diagnostics are effective only if they are accessible. Many of these innovations, however, are being developed and validated in homogeneous, high-income populations. A recent study has shown that, of 12,000 published neuroimaging studies, as many as 84% to 87% of study participants are non-Hispanic white. This disparity is in stark contrast with real-world settings, in which Black or Hispanic individuals are estimated to have a 1.5 to 2 times increased risk of developing dementia.

In the absence of diverse data, we risk developing diagnostics that could widen health disparities. Initiatives such as the Bio-Hermes trial from Global Alzheimer’s Platform (GAP) are working to create more well-characterized sample databases to increase representation from underrepresented groups. In their first cohort, 24% of the recruited patients came from underrepresented minorities, creating a more clinically relevant sample dataset to advance equitable diagnostics development. This is a great start, but additional efforts are needed.

Integration into existing clinical workflows also presents challenges. For instance, because blood-based biomarkers are new, many clinicians have limited experience interpreting the results and fitting them into existing diagnostic frameworks.

Cost is another factor: Blood-based tests are generally more affordable than PET scans, current pricing typically ranging from a couple hundred dollars to $1,200. However, reimbursement models to support widespread use are still evolving and require further generation of real-world evidence.

As these diagnostics scale, a coordinated effort will be needed to drive adoption, including demonstrating utility across diverse populations, integrating into clinical workflows, and generating evidence for reimbursement.

The Road Ahead

The evolution of Alzheimer’s disease diagnostics is at a critical juncture. Blood-based biomarkers, digital tools, and molecular profiling are transforming our ability to detect and treat Alzheimer’s disease earlier and more accurately than ever before. The recent FDA approvals of the Fujirebio and Roche blood tests are a landmark achievement but only the beginning. Continued investment and collaboration are essential.

Initiatives such as the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation’s Diagnostics Accelerator and the Alzheimer’s Disease Data Initiative are helping drive this shift by funding high-risk, high-reward projects and making data more widely accessible, both of which are critical for catalyzing innovation. Turning this innovation into impact will take coordinated action across science, policy, and health-care systems. As the world prepares to face a rising tide of dementia, the tools to detect it early are taking shape. Now it’s time to deliver them at scale.

Lydia Wu is a health and life sciences analyst at Gates Ventures, where she supports the Diagnostics Accelerator initiative in partnership with the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation.

Jennifer Panlilio is a program officer at the Diagnostics Accelerator at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF).

Melissa Lee is director of the Diagnostics Accelerator at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF).

Laura Nisenbaum is the executive director of drug development at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF).

Aishu Sukumar is an associate director in the health and life sciences team at Gates Ventures